First off let me clarify what I mean by “my” ultimate bug-out gear. I mean the ultimate bug-out gear for me in my personal situation. I live in the country, in the East Texas pine forest. The things that I feel I need in the way of bug out gear are not necessarily the same things you might need if you are an urban dweller, or if you live in a different climate. So, read what follows with that in mind.

When I was in elementary school we read about the Minute Men in history class. The Minute Men were citizen soldiers during the American Revolution that could leave their homes and go to battle on a minute’s notice. They had their rucksacks and blanket rolls packed and their flintlocks hanging above the door so that when the call to arms came they could grab their gear and go. Maybe this was the origin of my fascination with bug-out gear. I’ve evolved and honed my gear over the years, and this is what I have ended up with.

My bug-out gear consists of three major components or groups of components. They are (1) my gun, (2) my belt gear, and (3) my pack.

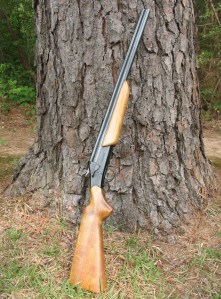

The gun that I have selected as my bug-out gun in a Savage, break-action, over and under combo gun. It has a .22 longrifle barrel over a 20 ga. shotgun barrel. The reason I chose this gun is because by using different ammunition in it, it can be used for such a wide variety of purposes. With .22 longrifles it is good for hunting small game. With .22 CB caps it’s as quiet as an air rifle. With 20 gauge number 7 1/2’s it’s a great bird and rabbit gun. With 20 gauge buckshot or slugs it is good for turkeys, deer, or self-defense. It’s light, sturdy, has few moving parts, and is an all around solid firearm.

My belt gear is just that; items that I carry on a leather belt around my waist. The belt itself is a two inch wide leather strap with a simple brass buckle. I carry a hunting knife on the right side of my belt. It is a carbon steel Russell Green River Knife with wooden slab handles. It is carried in a leather sheath. On the front right of the belt is a leather ammo pouch. It holds a tube of .22 longrifle shells, a tube of .22 CB caps, two 20 ga. #3 buckshot shells, and two 20 ga. slug shells. On the front left of my belt is a small pouch that holds a cigarette lighter and a compass.

The rest of my gear is carried in, or on, a small back-pack; what some people refer to as a day pack. The pack has several different compartments and pockets. It also has some straps for tying things to the outside.

In my next post I’ll go over the gear that I keep in my pack and how I store it.

When you need this gun things will be bad. Military rifles can be used for hunting, but their main purpose in life is to kill people. I hate the thought of having to do that, but I hate the thought of losing my family even more.

Modern military rifles (by this I mean WWII vintage and newer) are generally designed to be simple to operate, to be reliable under adverse conditions, to have man killing knock down power, and to hold plenty of ammo. Nearly all standard issue military rifles manufactured since WWII are at least semi-automatic, and some have full auto capability. Full auto models are illegal for civilian ownership unless you buy a special license. Most manufacturers of military rifles make semi-auto civilian versions of the same rifles. Personally I think semi-auto is enough. Full auto burns a lot of ammo, and most people can’t control the point of aim after the first few rounds. I believe that the U.S. military now advocates the use of three round burst rather than full auto. The volume of fire doctrines of Vietnam have pretty well been discredited; and accurate, aimed fire at a slower rate has been shown to be more effective in combat.

There are quite a few semi-auto versions of military rifles that are available on the civilian market. Probably the three most popular in the U.S. are the AR-15 (civilian version of the M-16), different variants of the Soviet SKS, and different variants of the Soviet AK-47. The Ruger Mini-14 is also very popular. It is a carbine size rifle that fires the .223 military round. All of these are good solid weapons.

The AR-15 is chambered for the .223 cartridge. It is well made, with good finish and close tolerances. Thirty round magazines are readily available and the ammo is moderate to cheap in price. Some feel that the close tolerances of the AR-15 make it subject to jamming, and it is probably not a good idea to use cheap ammo in it. The .223 round is considered by some critics to be too light for a military round. The biggest drawback to the AR-15 is its hefty price tag (in the $1000 range).

The SKS and its variants are a WWII vintage Soviet design. Many of the rifles were manufactured in China, Yugoslavia, and other Soviet block countries. The ones that I have seen and fired have been pretty well made. They are very utilitarian, nothing fancy, not the best finish, but they seem to be well machined and the one’s I fired were surprisingly accurate. The SKS holds 10 rounds of 7.62 x 39 ammo that is loaded via a stripper clip. This low ammo capacity and the method of loading are probably the biggest draw-backs to the SKS. You can buy after-market 30 round magazines for the SKS. I have not personally tried any of these, so I can’t comment on them. I have had a couple of reports of them being somewhat clumsy to use and not feeding all that well, but like I say I haven’t used one myself. One of the biggest pluses for the SKS is the price tag. At one time you could buy them for $89. Even in today’s market you can still find them for around $200.

The Soviet AK-47 and its many variants is the most widely manufactured firearm in history. The AK-47 fires the 7.62 x 39 round. It is commonly available with a 30 round magazine. The quality of the AK varies widely. The finish is nothing to write home about. Many of these rifles have laminated (read plywood) stocks and hand grips. The tolerances on the AK are very loose. Some of them actually rattle when fired. But it is because of the tolerances that the AK seems so impervious to jamming. I have seen a demonstration where a loaded AK is buried in the sand, pulled up out of the sand, and fired; without even blowing it off. AK’s vary in price along with the quality. You can pick up an AK variant for around $450. I have one of the Rumanian manufactured variants which is totally plain Jane. It is surprisingly accurate, and I have never had a jam.

The Ruger Mini-14 is a civilian weapon. The Mini-14 is manufactured by Strum Ruger and is a scaled down version of the M14 military rifle. Mini-14’s are chambered for the .223 U.S. military round and 5.56 x 45 NATO round. The Mini-14 is used by civilians and many police and security forces, but it is not in used by any of the world’s major military establishments. It is a good quality gun, as are all Ruger products, with good fit and finish. High capacity magazines and lots of after market accessories are available for the Mini-14. The price tag on the Mini falls somewhere in between the AK and the AR-15.

My recommendation for a homestead military rifle is the AK-47 or one of its variants. These guns are ugly but, in my experience, accurate and reliable. Ammo is plentiful and inexpensive ($5 for 20 rounds at this time). One of the best things about the AK is that you can buy two of them for the price of one AR-15 and have some change left over.

So that’s my picks for the five firearms that a homestead needs. You may disagree, and you may have good reasons; but I don’t think you would go too far wrong with the guns that I have recommended.

Hand guns and military rifles are a flashpoint for the anti-gun folks. They feel that there is no place for such things in a civilized society. I agree 100% and if I ever live in a civilized society I will be the first to give up my defensive firearms. I’m sorry, but there is violence in the world. People will try to hurt other people for no reason. People will try and take what you have. And this is when society is going along pretty well. Imagine what it would be like if the social order broke down completely. Does New Orleans during hurricane Katrina ring any bells with you? Most anti-gun folks live in cities. If they have a problem the police are usually no more than a few minutes away. Where I live there are four deputies to patrol 1600 square miles. By the time the law arrives, it’s all over. One night some guys were trying to break into my barn. I snuck up through the woods with a shotgun, crouched down in the brush, and fired a shot up in the air. They jumped in their truck and took off. I went back down to the house and called the sheriff to report what I had done. Their response was, “Do you want us to send somebody out.” “No,” I replied, “I just wanted to report what happened in case somebody calls in and says I was trying to kill them.” That’s how it works in the country. When people are spread out so thin, they have to learn to take care of themselves. So, I advocate the ownership of defensive weapons by sensible individuals that want to protect their families, their lives, and their property.

The handgun is not my first choice for home defense. I think a shotgun is far superior. A shotgun looks more intimidating, and a shotgun does not require as much skill or accuracy to use as a handgun. But, it’s kind of hard to carry a shotgun around with you all the time. A handgun, on the other hand, can easily be carried on the person. In Texas, where I live, any law abiding citizen can get a permit to carry a handgun; and many do. I don’t carry a handgun, but I do keep one in my truck. In Texas any citizen who is not a convicted felon, is not in the act of committing a felony, and who is not a member of a criminal organization, can carry a concealed handgun in their vehicle without any kind of permit. I would prefer to have a shotgun, but a shotgun is pretty hard to maneuver in a confined space like a vehicle.

So the question is, what kind of handgun? Do you want a revolver or an auto-loader? What size, what barrel length, what caliber. There are a lot of decisions to make. It used to be that law enforcement used nothing but revolvers because auto-loaders where considered to be too unreliable. The modern auto-loaders are pretty reliable, and they hold a lot more rounds of ammo. Nearly all departments issue auto-loaders now. As to size, select a handgun that fits your hand. When I’m looking at a handgun, the first thing I do (after making sure that it is unloaded) is to wrap my hand around it, hold it up into firing position, and place my index finger on the trigger. If it doesn’t feel right that’s as far as I go. If it’s not comfortable in my hand it doesn’t matter what other virtues it may have. Barrel length? Get the longest barrel that you can conveniently carry. The longer the barrel, the longer the sighting plane, and the more accurate the gun. When it comes to caliber, anything smaller than a .380 is too small. In Texas the law requires that a concealed handgun must be no smaller than .380 caliber.

I’m not going to recommend a specific handgun. That’s kind of like trying to tell people what brand of beer they should drink. The choice of a handgun is a very personal choice. I will recommend that you follow the guidelines mentioned above, and that if you select a revolver it be no smaller that .357 magnum (which will also shoot .38 specials).

If you choose an auto-loader I would recommend a 9mm because of the power and the wide availability of relatively inexpensive ammunition.

I carry an auto-loader; the Tarus PT-92. It is a clone of the Beretta 92 (in fact it is made on Beretta tooling). The PT-92 is medium in size, is double action, and holds 15 rounds of 9mm plus one in the chamber. Mine is accurate and I have had no jamming or other problems with it. Whatever handgun you choose, learn how to use it. That means lots of ammo and lots of range time. You don’t want to be trying to figure out where the safety is if you’re in a life and death situation

There are, in my opinion, three kinds of people in the world with regards to guns. There are people that hate guns. They think that guns are inherently evil and that the world would be a better place if there were no guns at all. Then there are people that love guns. They collect guns, they clean guns, they read about guns, they go to gun shows, they just generally enjoy everything about guns. Some of these people, I have noticed, enjoy having guns more than they enjoy shooting guns; but hey, to each his own. The third kind of people are folks that see guns as being tools that are useful to perform specific tasks. These people have a chainsaw to cut firewood, they have garden tools to raise food with, they have hand tools to build things with, and they have guns to hunt with and to protect their families.

If you tend to be a no gun type person you’re probably not reading this anyway, and if you are a gun lover you already know more about this stuff than I could every tell you; but if you are a guns-as-tools kind of person then this post is for you.

It is my belief that the average American homestead only needs five guns to handle any possible situation. So I am going to outline what my choices are, why I have selected these particular guns, and the circumstances under which each of these guns would be useful.

First on my list is a good Shotgun. The shotgun is like the multi-tool of the gun world. Depending on the ammo that you use the shotgun can be a small game hunter, a medium size (deer) game hunter, or a home defense weapon. You can use number eight to hunt dove, quail, and squirrels; number sixes for rabbits, coons, and possums; and number fours for turkeys and ducks. If you load up with 00 shot or slugs you can take deer or wild hogs out to about thirty yards or so. A shotgun loaded with 00 is an outstanding home defense weapon. No pinpoint accuracy is required and the knock down power is tremendous.

Shotguns come in 10 gauge, 12 gauge, 28 gauge, 20 gauge, 16 gauge, and .410. The 10 gauge is expensive, ammo is rare, and it has more recoil than the average shooter is comfortable with. Twenty-eight and sixteen gauges are somewhat rare, ammo is not readily available, and their recoil is not much different than the 20 gauge. Because of their relatively light load of shot, .410’s require a lot more accuracy; and the ammo is expensive. The 12 gauge and the 20 gauge are the most common and the ammo is widely available and cheap. I personally like a 12 gauge. If you want a little less recoil go with the 20.

Shotguns come in single shot, double barrel, bolt action, pump, and semi-auto. The single shot leaves you with no back-up shot. Doubles are expensive, and you have only two shots. Bolt actions hold several shells, but they are often temperamental loaders. Pumps and semi-autos are the most common. I personally prefer the pump, but that’s just me.

My recommendation for the homestead shotgun is the Remington 870 pump. This is a very reliable, moderately priced shotgun that has stood the test of time.

The number two gun on my list is a good Small-Bore Rifle. By this I am referring to the .22 caliber rifle. The .22 is the most widely owned gun in America. A good .22 does not break the bank when you buy it, and the ammo is in expensive and very common. The thing I like best about the .22 is its low signature; that is to say, it doesn’t make much noise. You can use a .22 to hunt squirrels, rabbits, and other small game without everyone in the county hearing you. Remember, if times go bad, the noise of gunfire can draw attention that you don’t want. Twenty-twos come in bolt action, lever action, punp, and semi-auto. Bolt actions and semi-autos are the most common and are comparable in price. When you buy a .22, ditch the cheap scope that comes on it and replace it with a good variable power scope.

My recommendation for the homestead small bore rifle is the Ruger 10-22. This is a very reliable, medium priced, semi-auto. It and the Marlin are probably the most popular semi-auto .22’s on the market today. The Ruger costs a little more than the Marlin, but I think it is a better quality gun.

The third gun on my homesteader’s list is the Large-Bore Rifle. This is the gun that is commonly referred to as a deer rifle. The large-bore is used to take medium size game that is too far away for the shotgun. If you live in open country you will probably not get close enough to a deer to use a shotgun, but the deer rifle will reach out three-hundred yards to take that venison home. The large-bore can also be used for hogs, antelope, sheep, and other game. A good scope is a must for the large-bore. The most common calibers are .243, .30-30, .308, .270, and .30-06. Military rifles that are chambered for 7.62 x .39 or larger will make a serviceable hunting rifle if they are equipped with a scope. I personally have a WWII vintage .303 Enfield in bolt-action with a good scope that serves my purposes just fine.

Large-bore rifles commonly come in bolt action, lever-action, and semi-auto. The Marlin and Winchester lever-actions in .30-30 are probably two of the most common and most affordable large-bore rifles sold in America today.

My recommendation for the homestead large-bore rifle is the Remington 700 in .270 or .30-06. This is a reliable bolt-action rifle that carries a moderate to expensive price-tag depending on the grade.

If price is a big factor you will not go wrong with the Marlin lever-action in .30-30. I prefer the Marlin over the Winchester because the Marlin has a side ejection port which makes it much easier to mount a scope on the Marlin.

If the world was a friendly place, if crime didn’t exist, and if there was never any chance of the social order breaking down; we could stop right here. But, unfortunately, we live in the real world, so I feel compelled to include two defensive guns on my list of five. I will address home defense handguns and military style rifles in my next posts.

I was recently at a local grocery store and I saw that they had a sign saying “yucca root” for sale. Someone had made a mistake and labeled this root as yucca when it was actually yuca with one “c”. Yuca is another name for cassava which is a potato-like root that is cultivated in tropical regions throughout the world. Yuca (cassava) and yucca (yucca louisans) are not the same plant. The root of yucca (yucca louisans) contains a high concentration of saponin. Saponin is an anti-bacterial, anti-fungal, lathering agent. In other words, it is soap. If you eat yucca root you will get sick as a dog.

I can’t help but wonder how many people saw that sign in the grocery store and thought, “Hey, I have yucca plants growing around my house. I think I’ll dig up a root and try it.”

So far as I know the only part of a yucca plant that is edible are the young flowers which I have read can be used in salads. I’ve never tried this personally so I can’t verify that this is true.

The yucca is an incredibly useful plant. You can use it to make fire starting tools, you can use the dried leaves for tinder, you can use the roots and leaves to make soap, you can use the leaves to make cordage, you can make yucca leaf baskets, you can make hats and sandals from yucca leaves, but, you CANNOT eat yucca. So don’t try it; you won’t like it.

When the sheath has dried, take three or more small nails and tack it down on a board. This will hold the sheath firmly in place while you take a leather awl and poke holes around the outside edge of the sheath. Pictured below: Punching holes in knife sheath that is tacked down on a board to hold it in place.

Next you will need to sew the sheath together using artificial sinew, linen, or some other type of heavy thread. Sew all the way around the sheath in one direction and then sew back in the other direction. This will give you a solid line of stitching. Tie the ends of your thread together with a triple knot and use the point of your awl to shove the knot between the front and back layers of raw hide so that the knot is hidden. Pictured below: Sewing the sheath first in one direction then back in the other.

When the sheath is sewn together you can take a pair of sharp scissors and cut the outside of the welt into fringe. Pictured below: top, Cutting fringe;bottom, fringe completed.

You could call the job done here and put a neck cord on the sheath; but if you want a more fitted look to the sheath you need to put it in some water and let it soak over night and soften back up. Pictured below: Sheath soaking in water.

While the sheath is soaking you can prepare your knife for insertion into the wet sheath.

First take some masking tape and cover the point and cutting edge of the knife.

Next wrap the knife inside of a sealed plastic bag and place some tape around the bag to hold it in place. The tape covering the point and blade will keep the knife from cutting through the bag.

When the sheath is thoroughly soaked and pliable, push the covered knife down into it, then take a couple of nails and tack down the top edge of the sheath so that it doesn’t wrinkle up as it dries. Set the knife and sheath aside to dry for a couple of days.

After the sheath dries you can remove the knife and take the bag and the tape off of it. You will need to trim up the top part of the back and punch a couple of holes in it where you can attach a neck cord. Twisted or braided brain tan leather makes a nice cord. Pictured below: Finished neck knife sheath.

And there’s your finished product, a good looking neck knife sheath that you made yourself. No one would ever guess that it started out life as a dog’s chew toy.

I have a nice little handmade knife that I bought at Mansker’s Station a couple of years ago. I bought it for a neck knife, but it came without a sheath, so I decided to use some chew-bone rawhide to make a sheath for it. This is how I made the sheath, and it is the way that you can make one if you ever have the need.

First Take a couple of pieces of wet chew-bone rawhide (see the previous post for more on this) and nail them out on a board to dry. Pictured below: Dried chew-bone rawhide and knife.

When the rawhide is dry, lay your knife down on it and draw a line that is about a half inch out from the blade of the knife. If you want the handle to go part way down into the sheath, draw the lines on up about an inch and a half above where the blade begins. Pictured below: Rawhide with line drawn around blade.

Now take some heavy duty scissors and cut out what will become the back of the sheath. Pictured below: Sheath back cut out.

When you have the back cut out, lay it down on your other piece of rawhide and trace around it to outline what will become the front of the sheath. Don’t make the front come up as high as the back so that you will have a place to attach the neck cord to you finished sheath. Pictured below: Using back of sheath as a pattern to trace out sheath front.

Now cut out the front of the sheath. Pictured below: Front and back of sheath cut out.

Next you are going to make a welt to sew in between the front and back of the sheath. The welt serves to keep the knife blade from cutting through the stitches that hold the sheath together. You can make the welt flush with the outside of the sheath; or you can, as I have here, cut the welt so that it sticks out from the edge of the sheath. If you do this you can come back after the sheath is sewn together and cut the exposed part of the welt into fringe. You want your welt to be about a quarter inch inside of the sheath, so use your pencil to draw a guide line before you cut the welt. Pictured below: Lines draw for welt. The pencil is pointing to the line that will be flush with the sheath. Leather inside of the line will be the welt. Leather outside the line will be fringe.

When the welt is cut out, you can use some glue and glue the welt in between the front and the back of the sheath. Set a couple of books on top of the sheath to keep everything in good contact and let it dry over night. Pictured below: top, Welt cut out; middle, Applying glue to welt; bottom, Front of sheath, welt, and back of sheath glued together.

In the next post we will sew the sheath together, form fit it to the knife, and finish it out.

So you’re interested in learning some wilderness survival skills, and you’d like to make a few projects that require some rawhide; but you live in the city, you don’t hunt, and you don’t have any friends that hunt. How are you going to get any rawhide? Well, you could go on-line and order some, but the easiest way is to go down and buy some at the grocery store. “What,” you say. “Are you nuts? What kind of hillbilly place do you live where they sell rawhide at the grocery stores?” Well my friend, they sell it at your grocery store too.

All you have to do is go to the pet food isle and buy yourself a nice doggy chew bone. These bones are made of rolled up beef rawhide. Pictured below: Small chew bone.

To make the rawhide usable for your purposes just soak the bone in a tub of water over night. Pictured below: Chew bone soaking in water.

The next morning it will be soft and pliable. Untie the knots in the ends and unroll the wet rawhide. You won’t have a big sheet of hide like if you made your own, and it won’t have that nice brown color, but it is big enough to cut into thongs for attaching an axe head or a spear point. Pictured below: top, Chew bone just removed from water; bottom, this chew bone was made of two small pieces of rawhide.

Use small nails to stretch the rawhide out on a board and let it dry for a day or two. I’m going to use these pieces of rawhide to make a neck-knife sheath. Pictured below: Chew bone rawhide stretched out to dry along with the knife that I will be making a sheath for.

I have also seen some pretty nice bullet pouches made out of chew bone rawhide. This type of rawhide is not good for making bowstrings and other small cordage. It is too thick, and it doesn’t seem as strong as deer rawhide. But, maybe this will help you get a few smaller projects done until you can make some of your own rawhide.

Many people know that you can make soap from yucca root, but digging up a yucca plant is a lot of work and it kills the plant. The active ingredient in yucca soap is saponin. Saponin is the an anti-bacterial, anti-fungal chemical that foams when it is shaken up. High concentrations of saponin are found in yucca root, but saponin is also found in the leaves of the yucca.

Here’s how to make yucca soap and avoid killing the yucca plant:

Cut a handful of yucca leaves.

Use your knife to scrape the waxy, green skin off of the leaves.

Place the scrapings in a sealable container with some water.

Shake the container vigorously for several minutes.

Pour the liquid off into another container and discard the scrapings.

The liquid can be used as hand soap, shampoo, disinfectant wash, laundry soap, or dishwashing soap.